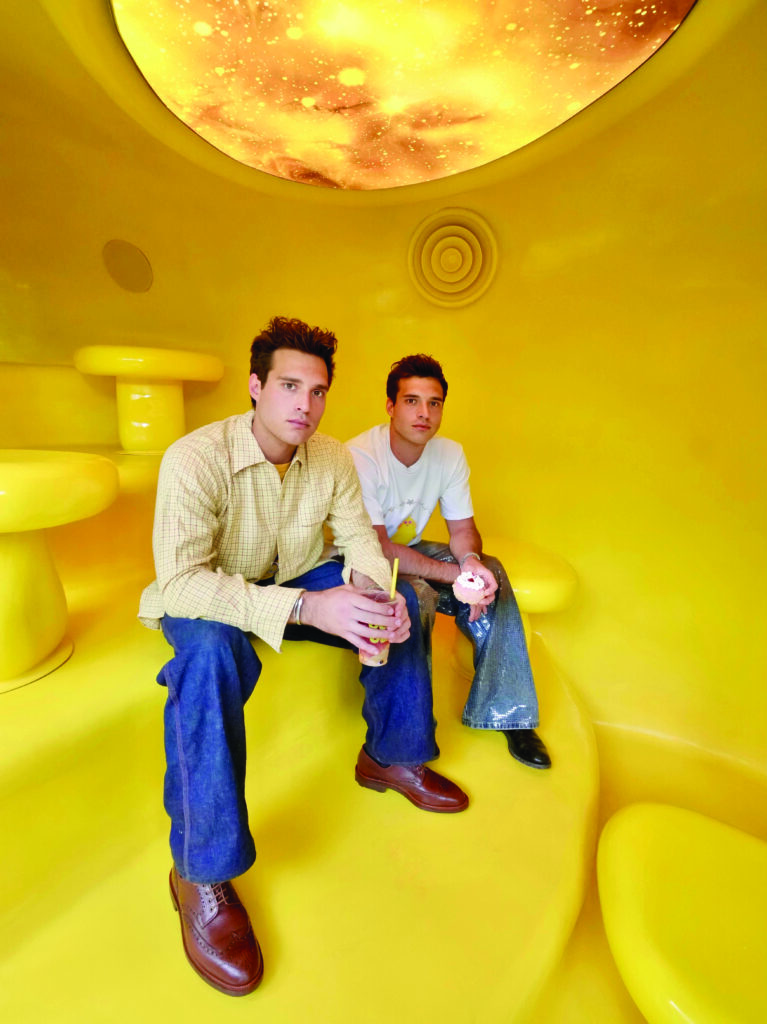

Oneohtrix Point Never, whose real name is Daniel Lopatin, is one of the most revolutionary and influential producers, composers, and creators in contemporary music. He is an alchemist of experimental electronic sound, using synthesisers to fuse and create unheard sonic forms. His early work Eccojams Vol.1 became a pioneer of the vaporwave genre; later albums such as R Plus Seven and Garden of Delete redefined ambient and experimental music in the digital era. Beyond his solo projects, he has collaborated with top artists including Nine Inch Nails, Iggy Pop, Charli XCX, and The Weeknd; he also composed film scores for Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring and the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems and Good Time. The soundtrack for Timothée Chalamet’s upcoming table-tennis biopic Marty Supreme is also produced by him.

Oneohtrix Point Never recently released his 11th studio album, Tranquilizer, with 15 tracks that continue his exploration of forgotten media and transform it into work rooted in the present moment. The album originated when he discovered that a massive collection of 1990s and 2000s CD samples had nearly disappeared from the Internet Archive. Those lost-and-found commercial audio clips became the foundation of the record. He has long been drawn to functional, marginalised, and overly commercial sounds, and applies Marcel Duchamp’s “found object” philosophy to reinterpret everyday audio from advertising, games, or corporate media, extracting an unsettling density from fragmented memories. Digital decay and obscurity intertwine with tranquil atmospheres; ordinary textures give way to emotional overload; the real and the unreal merge. In this GQ Hong Kong interview, Oneohtrix Point Never openly shares details of the new album, his musical inspirations, and his process in creating film soundtracks.

What music did you listen to while growing up? Which album still inspires you to this day?

When I was really young: Beatles, Stevie Wonder, Return To Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Sting, in my early teens I listened to a lot of alternative rock. In high school a lot of hip hop and electronic music. DJ Premier’s Crooklyn Cuts I-IV stays with me more than a lot of other stuff

What has influenced your musical style the most?

Music that I didn’t choose to listen to.

Your musical career is extremely prolific. From the beginning until now, how has your sound evolved and shifted across different genres?

Boredom or burnout on one thing or other and switch gears, just like anyone else.

What specifically draws you to the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s?

70s’ melodicism, 80s’ technology and 90s’ attitude

In the age of AI and the internet, how does information overload reflect in your creative process?

It’s a colour I use to paint with.

In your view, what is the beauty of synthesisers?

Its beauty is similar to the beauty of a loom, a brain, a concept, or a kitchen.

For Tranquilizer, how do you connect the archive of the commercial sample library to the present?

I’m in the present so I’m the connection.

How would you describe the spirits of commercial, functional music? How did you use custom software to rework on it?

I don’t use custom software I use regular everyday software like Ableton, samplers, plugins and other stuff anyone can get. The spirit of functional music is in their function. As a readymade object the artist manipulates the object to change its spirit.

The album moves from the weightless calm of tracks like Lifeworld into more embodied territory in Cherry Blue and Rodl Glide. Can you walk us through the emotional or sonic arc you envisioned between these songs?

It’s just intuition, and sequencing an experience that makes sense to me. But I wouldn’t want to explain that, it’s like explaining the plot of a movie that doesn’t have any plot. It’s meant to be felt not explained.

What’s the difference between working on your own projects and collaborating on pop music?Collaboration means compromise and empathy. Solo music is a conversation I can only have with myself and my heart.

Can you walk us through the process of creating an OST for a movie?

I watch the film, I spot the film with the director, we commit to a list of cues for me to work on, and I begin to write — and there’s a lot of discussion back and forth until the music is approved and it’s time to mix the score, first for the film and then a whole other arrangement pass, mix and master to create the OST.

Without spoiling the score, how does the OST for Marty Supreme all come together? Can you give us a hint of what it will be like?

I wish I could but it’s a fantastic surprise and I’ve very proud of it. It’s the best score I’ve ever made for Josh, and he very clearly has made the best film of his career.

Last but not least, Long Road Home with Caroline Polachek is one of my favourites of all time. Can you tell us more about the story behind it?

I made it during Covid, when I felt that a lot of people had strayed away from what home is really about, while being stuck inside their homes.

Image: Aidan Zamiri